Pandita Ramabai is one of the greatest women that India ever saw. The Sanskrit scholars of Calcutta University conferred on her the titles of "Sarawati" and "Pandita” after being impressed by her knowledge in Hindu scriptures. Yet she was deeply dissatisfied by Hinduism. Her book The High Caste Indian Woman is considered as the Indian feminist manifesto. Yet she was not a feminist in the current meaning of feminism. She imitated her guru and savior Jesus Christ and became one of the greatest names in India. Read her story in her own words.

Pandita Ramabai is one of the greatest women that India ever saw. The Sanskrit scholars of Calcutta University conferred on her the titles of "Sarawati" and "Pandita” after being impressed by her knowledge in Hindu scriptures. Yet she was deeply dissatisfied by Hinduism. Her book The High Caste Indian Woman is considered as the Indian feminist manifesto. Yet she was not a feminist in the current meaning of feminism. She imitated her guru and savior Jesus Christ and became one of the greatest names in India. Read her story in her own words.

My father, though a very orthodox Hindu and strictly adhering to caste and other religious rules, was yet a reformer in his own way. He could not see why women and people of Shudra caste should not learn to read and write the Sanskrit language and learn sacred literature other than the Vedas.

He thought it better to try the experiment at home instead of preaching to others. He found an apt pupil in my mother, who fell in line with his plan, and became an excellent Sanskrit scholar. She performed all her home duties, cooked, washed, and did all household work, took care of her children, attended to guests, and did all that was required of a good religious wife and mother. She devoted many hours of her time in the night to the regular study of the sacred Puranic literature and was able to store up a great deal of knowledge in her mind.

The Brahman Pandits living in the Mangalore District, round about my father's native village, tried to dissuade him from the heretical course he was following in teaching his wife the sacred language of the gods. He had fully prepared himself to meet their objections. His extensive studies in the Hindu sacred literature enabled him to quote chapter and verse of each sacred book, which gives authority to teach women and Shudras. His misdeeds were reported to the head priest of the sect to which he belonged, and the learned Brahmans induced the guru to call this heretic to appear before him and before the august assemblage of the Pandits, to give his reasons for taking this course or be excommunicated. He was summoned to Krishnapura and Udipi, the chief seat of the Madhva Vaishnava sect.

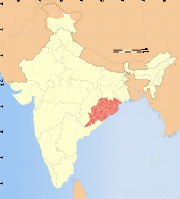

My father appeared before the guru, the head priest, and the assembly of Pandits and gave his reasons for teaching his wife. He quoted ancient authorities, and succeeded in convincing the guru and chief Pandits that it was not wrong for women and Shudras to learn Sanskrit Puranic literature. So they did not put him out of caste, nor was he molested by anyone after this. He became known as an orthodox reformer. My father was a native of Mangalore district, but he chose a place in a dense forest on the top of a peak of the Western Ghats, on the borders of Mysore State, where he built a home for himself. This was done in order that he might be away from the hubbub of the world, carry on his educational work and engage in devotion to the gods in a quiet place, where he would not be constantly worried by curious visitors. He used to get his support from the rice-fields and coconut plantations which he owned.

The place he had selected for his home happened to be a sacred place of pilgrimage, where pilgrims came all the year round. He thought it was his duty to entertain them at his expense, as hospitality was a part of his religion. For thirteen years he stayed there and did his work quietly, but lost all his property because of the great expense he incurred in performing what he thought was his duty. So he was obliged to leave his home and lead a pilgrim's life.

My mother told me that I was only about six months old when they left their home. She placed me in a big box made of cane, and a man carried it on his head from the mountain top to the valley. Thus my pilgrim life began when I was a little baby. I was the youngest member of the family. Some people honoured him for what he was doing, and some despised him. He cared little for what people said and did what he thought was right. He taught and educated my mother, brother, sister, and others.

A Unique Education

When I was about eight years old, my mother began to teach me and continued to do so until I was about fifteen years of age. During these years she succeeded in training my mind so that I might be able to carry on my own education with very little aid from others. I did not know of any schools for girls and women existing then, where higher education was to be obtained.

Moreover, my parents did not like us children to come in contact with the outside world. They wanted us to be strictly religious and adhere to their old faith. learning any other language except Sanskrit was out of the question. Secular education of any kind was looked upon as leading people to worldliness which would prevent them from getting into the way of Moksha, or liberation from everlasting trouble of reincarnation in millions and millions of animal species, and undergoing the pains of suffering countless millions of diseases and deaths.

To learn the English language and to come in contact with the Mlenchchas, as the Non-Hindus are called, was forbidden on pain of losing caste and all hope of future happiness. So all that we could or did learn was the Sanskrit grammar and dictionaries, with the Puranic and modem poetical literature in that language. Most of this, including the grammar and dictionaries, which are written in verse form, had to be committed to memory. Ever since I remember anything, my father and mother were always traveling from one sacred place to another, staying in each place for some months, bathing in the sacred river or tank, visiting temples, worshipping household gods and the images of gods in the temples, and reading Puranas in temples or in some convenient places. The reading of the Puranas served a double purpos

e.

The first and the foremost was that of getting rid of sin, and of earning merit in order to obtain Moksha. The other purpose was to earn an honest living, without begging. The readers of Puranas. Puranikas as they are called- are the popular and public preachers of religion among the Hindus. They sit in some prominent place, in temple halls or under the trees, or on the banks of rivers and tanks, with their manuscript books in their hands, and read the Puranas in a loud voice with intonation, so that the passers-by, or visitors of the temple might hear. The text, being in the Sanskrit language, is not understood by the hearers. The Puranikas are not obliged to explain it to them. They mayor may not explain it as they choose. And sometimes when it is translated and explained, the Puranika takes great pains to make his speech as popular as he can by telling greatly exaggerated or untrue stories. This is not considered sin, since it is done to attract common people's attention, that they may hear the sacred sound, the names of the gods, and some of their deeds, and be purified by this means.

When the Puranika reads Puranas, the hearers, who are sure to come and sit around him for a few moments at least, generally give him presents. The Puranika continues to read, paying no attention to what the hearers do or say. They come and go at their choice. When they come, the religious ones among them prostrate themselves before him and worship him and the book, offering flowers, fruits, sweetmeats, garments, money, and other things. It is supposed that this act brings a great deal of merit to the giver, and the person who receives does not incur any sin. If a hearer does not give presents to the Puranika, he loses all the merit which he may have earned by good acts. The presents need not be very expensive ones, a handful of rice or other grains, a pice, or even a few cowries, which are used as an invitation. So we went to the Christian people's gathering for the first time in our lives.

We saw many people gathered there who received us very kindly. There were chairs and sofas, tables, lamps. all very new to us. Indian people curiously dressed like English men and women; some men like the Rev. K.M. Banerji and Kali Charan Banerji, whose names sounded like those of Brahmans but whose way of dressing showed that they had become "Sahibs", were great curiosities. They ate bread and biscuits and drank tea with the English people and shocked us by asking us to partake of the refreshment. We thought the last age, Kali Yuga, that is, the age of quarrels, darknt'ss, and irreligion, had fully established its reign in Calcutta since some of the Brahmans were so irreligious as to eat food with the English.

We looked upon the proceedings of the assembly with curiosity but did not understand what they were aboUt. After a little while one of them opened a book and read something out of it and then they knelt down before their chairs and some said something with closed eyes. We were told that was the way they prayed to God. We did not see any image to which they paid their homage but it seemed as though they were paying homage to the chairs before which they knelt. Such was the crude idea of Christian worship that impressed itself on my mind. The kind Christians gave me a copy of the Holy Bible in Sanskrit and some other nice things with it.

Two of those people were the translators of the Bible. They were grand old men. I do not remember their names, but they must have prayed for my conversion through the reading of the Bible. I liked the outward appearance of the Book and tried to read it but did not understand. The language was so different from the Sanskrit literature of the Hindus, the teaching so different, that I thought it quite a waste of time to read that Book, but I have never parted with it since then.

Next: Deeper Hindu Studies and Skepticism

{moscomment}

🙂

i had always wanted to read about Pandita Ramabai. Its a nice thing to publish her autobiography. Thank you.

I am waiting for the next one, “Deeper Hindi studies and skepticism”

By..The Indian Feminist

Rambai was an awesome woman. Thanks for publishing her bio. I am also waiting for the next one. I will check it on Monday.

“Her book The High Caste Indian Woman is considered as the Indian feminist manifesto. Yet she was not a feminist in the current meaning of feminism.”

Either she was a feminist or she was not? Can someone be a feminist and a Christian? Explain. U guys are hillarious. :grin

God is constantaly on work to let truth replace every form of falsehood. Was Pandita Ramabai related to Swami Dayanand who founded Arya Samaj sect?

I read it in some magazine that both were planning to marry but she insisted to speak out truth to Dayanad which he denied.

Pandita Rama bai, was very keen to read Vedas and related literature. She could not find any body who was willing to help her, till she heard of Swami Dayanand. At that point of time Swami ji was staying in Meerut. Ramabai came to Meerut and stayed there for some months learning about Vedic Dharma from Swami ji. Swami ji wanted her to take charge of work related to women in India -She in fact did make a start by opening Arya Mahila Sangh. In the mean while Ramabai’s brother called her back to Calcutta, and married her off. Ramabai in her work with women felt the need to learn allopathic medicine. Christian missioneries offered to send her to England to study medicine, if she became a Xtian. She took Xstianity and went to England. She could not pursue her medical education, due to some hearing defficiency. Instead she fended for herself by taking hindi/sanskrit classes in England. From there she moved to US. But her brand of Xstianity was said to be very different, as a Xstian is reported to have remarked that Ramabai was a Xstian dream gone sour.

it is wonder full